CDM Myth 2: External Standards in your CDM

Some time ago an anonymous visitor showed interest in the relationship between a CDM and an external standard. I promised to come back to that subject. Here's my first attempt to try to explain this relationship.

CDM Myth 2: External Standards in your CDM

An often heard idea about the creation of a CDM is that you can add the contents of a relevant external standard in your CDM just like that, thereby efficiently creating a CDM with high quality content.

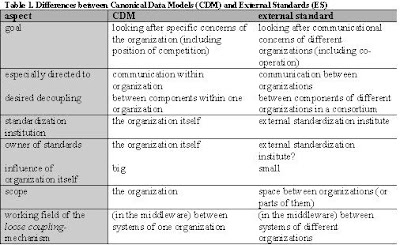

CDM’s and external data- or communication standards (abbreviated ‘ES-es’ in my terminology) are both collections of agreements, ’standards’ that can be applied in a loosely coupling environment. But there are important differences as well, as Table 1 indicates.

These differences require different appliances of the standards. The goal people had in mind when designing their external standards was to enhance the communication processes between organizations, not to standardize an organization internally. This goal is comparable to the one of the artificial language Esperanto. This language was not created as a replacement for any existing natural language in use at the time, but to offer people a second language to be used for communication between persons speaking different native languages.

Because of the fact that external standards are not focused on looking after the interests specific for your own organization, they shouldn’t be incorporated as an accepted fact in any organization- specific CDM without thorough consideration. The only correct way to use an ES for the construction of a CDM is by identifying interesting parts in it, screening these parts for desirability and for consistency with existing standards, guidelines and principles in your organization, and incorporating them as ‘borrowed ideas’ in your CDM, in accordance with the construction principles valid for this CDM. If done this way, an organization can keep her self determination and her own identity, and she can determine and realize her own competition strategy.

It’s important that the dependency between the ES and the CM be broken immediately after the borrowing of the ideas has been completed. The CDM should not be regarded as being ‘standardized’ by this external standard, it has only borrowed some useful ideas, that’s all. See Picture 1 for an illustration of the process. Keeping the dependency endangers the organization’s flexibility and self determination or sovereignty. Changes in the ES or a choice for another ES would then have to be carried through in the CDM as well. Moreover, your CDM could then be changed only after the change is adopted by the ES first, which is something no organization can force a standardization institute to accept.

Complications in the use of an ES as a CDM building block

In addition to this flexibility issue discussed so far, there are a few reasons to be very careful with the use of an ES as a CDM building block.

Mutual inconsistencies. There can easily be many inconsistencies between different external standards. This makes blindly incorporating an ES into a CDM a risky thing to do. One cause for such inconsistencies is the fact that ES-es often overlap. This might probably not happen very frequently with regard to their model of the primary domain they’re intended for, for example ‘transportation by train’ or ‘postal code representation’, but there’s another tricky property to many ES-es: they don’t only standardize on only one dimension. I’ve seen many standards that, in addition to standardizing the data involve in their domain, offered standards about many other things as well, like message structures, the language chosen to represent the messages in (XML, for example) and the precise way in which the messages should be modeled in this language (something like ‘best practices XML’). It’s not hard to see that these standards do not agree on all dimensions. To make things even more complicated, many organizations, like we do, probably have their own construction principles on some of these dimensions. A way out of this inconsistency web is to only borrow ideas from within one single dimension, ideas that do not cross any dimension borders, and incorporate only content that is consistent with the standards you happen to adhere to yourself.

Weak semantic standardization. A second complication pops up when an external standard is only weakly standardized with regard to data semantics, which actually means it is ambiguous. The result of this is that parties who adopted such a standard will likely use it in different ways. Although at first sight there seems to be nothing wrong, both parties using exactly the same technical message structure and the same symbols for representing their data, there may be a ‘hidden semantic problem’ at work. Semantic harmonization requires quite a thorough scrutiny of each parties’ precise semantics. This is not an easy thing to perform. So, although these external standards are called ‘standards’, it seems some of them are more standardized than others. I expect this to happen rather often. It seems at least wise to be very critical about the so-called ‘intended interpretations’ of the standardized messages involved, and also about the semantics of the data that are actually transmitted using these messages.

1 Comments:

Thanks for clearing this up - it's so clear now!

Post a Comment

<< Home